Michael Lengefeld

What is this research about?

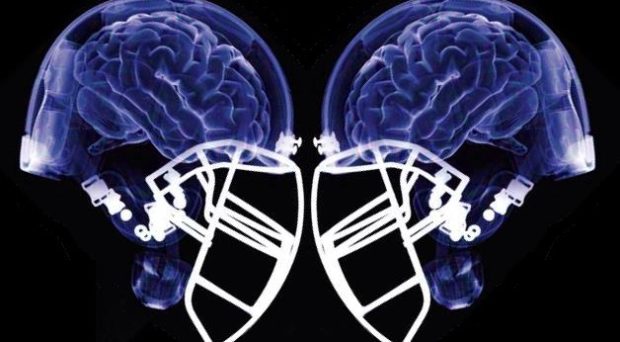

Scientific knowledge of head injury resulting from sport dates to the 1800s.

Between 2007 and 2014, all U.S. states passed concussion legislation regulating

youth sports participation.

Why were some U.S. states slower than others to pass concussion laws

with return to play restrictions?

What did the researcher do?

The researchers located and analyzed data from 50 U.S. states on concussion laws and high school sports

participation rates. Discourse around concussions has focused on youth athletes as a population at risk,

which require risk-reduction medical policies to protect them. The amount of

youth sport participation in a state identifies a key group of at-risk

individuals. If a disease only affects a few individuals, it is less likely that medically informed laws will be passed.

The concussion issue was framed by the NFL and others in terms of youth safety

across all activities.

The constituency hypothesis: States with higher

levels of youth sport participation will adopt concussion legislation earlier.

Alternatively, youth sport involvement could delay the adoption of concussion laws. Powerful social organizations and actors influence culturally significant activities.

Cultural norms regarding youth sport have undermined the push for greater attention to

head injuries. Interwoven themes of masculinity, violence and being "headstrong" have a long history in the NFL, and

these same themes resonate in American football culture at all levels of competition.

Consider the perspective of Chicago Bears wide receiver Brandon Marshall when commenting on

the Miami Dolphins "bullying" scandal.1

The resistance hypothesis: States with higher levels of youth sport participation will adopt concussion

legislation later.

Source: YMCA of North Carolina